Our first steps in Toledo weren’t rushed. Our guide paused at the beginning of the tour, right where three simple tiles embedded in the cobblestone spell it out plainly:

Judería de Toledo,

The Jewish Quarter,

and in Hebrew,

רובע היהודי בטולדו.

And just like that, he introduced us to the heart of this ancient city’s identity: Toledo is the City of the Three Cultures.

For centuries, Muslims, Jews, and Christians lived side by side here—not just coexisting, but thriving together. It wasn’t always peaceful, and it didn’t last forever, but for a remarkable stretch of time, Toledo was one of the few places in Europe where all three religions helped shape the culture, the language, and even the architecture. This is what gives Toledo its soul.

Medallions of Memory

As we wound our way through the narrow lanes of the Jewish Quarter, we began to notice small ceramic medallions tucked into the pavement.

One shows the menorah, the ancient symbol of Judaism.

Another spells out “chai” (חי) in Hebrew, which means life.

They act like silent breadcrumbs, guiding visitors through a once-vibrant community that included poets, philosophers, and scholars.

Our walking tour through Toledo’s winding stone streets eventually led us to a small, unassuming church that holds one of Spain’s most treasured artworks—The Burial of the Count of Orgaz by El Greco. Located in the Iglesia de Santo Tomé, the painting is still displayed exactly where it was commissioned to hang in 1586.

We stepped into the dimly lit chapel and were instantly drawn into the drama and mysticism of the scene. El Greco masterfully depicts the legend of Count Orgaz, a nobleman so beloved that Saint Augustine and Saint Stephen are shown descending from heaven to personally bury him. The lower half of the painting shows a solemn and highly detailed earthly ceremony, while the upper half bursts into swirling heavenly forms. It’s El Greco at his best—elongated figures, otherworldly light, and spiritual intensity.

One of the most moving touches? The small boy in the lower left corner, believed to be El Greco’s son. His hand points directly to the miracle, guiding our eyes just in case we missed it.

Our guide encouraged us to step back and absorb the full vertical drama of the work—how it visually connects earth and heaven. You don’t just see the painting, you feel it. Standing in that quiet space, surrounded by centuries of devotion, we understood why El Greco remains one of Toledo’s most enduring voices.

From the winding lanes of the Jewish Quarter, we made our way to one of Toledo’s most remarkable spaces—the Synagogue of El Tránsito. Commissioned in the 1350s by Samuel ha-Levi, treasurer to King Pedro I, the building reflects a moment in history when Jewish life flourished in Toledo under royal protection.

Inside that building—now a museum—we saw intricate Islamic-style arches framing a burgundy curtain embroidered with Hebrew letters. It’s where the Torah scrolls were once kept. The plaster filigree overhead mimics the style of mosques, a powerful visual reminder of how deeply the cultures intertwined. Jewish faith, Muslim design, and Christian rule—all represented in one room.

This intricately patterned floor mosaic is part of the preserved remains inside the Synagogue of El Tránsito. It features geometric designs in multicolored stone—an example of Mudejar art, a style developed by Muslims living under Christian rule. This style is unique to Spain and showcases the blending of Islamic art and Jewish heritage in Toledo before the 1492 expulsion of the Jews.

After we left the museum, Javier surprised us with a Toledo specialty—marzipan. Though widely made throughout Spain, Toledo is especially famous for its version, traditionally made by cloistered nuns. It’s a sweet symbol of the city’s layers of cultural heritage, as it likely has roots in both Muslim and Jewish confectionery.

Right after our pastry break, we paused outside a local knife shop where a woman stepped out to greet us. She proudly showed off a hand-forged blade, wrapped in ribbon, and explained Toledo’s centuries-old tradition of sword-making. These blades, known for their strength and flexibility, were once prized by Spanish knights and are still crafted by artisans today.

She passed the knife around so we could feel its weight—simple, elegant, and a symbol of the city’s craftsmanship. It was a quick but meaningful stop that gave us a deeper appreciation for Toledo’s layered identity—just before we turned the corner to the cathedral.

Eventually, we made our way to Toledo’s cathedral, built in the 13th century over what had once been a mosque—and before that, a Visigoth church. You could feel the history layered in the stone.

As we stepped inside, our first stop was the Treasury. Our guide joked, “This is where the phrase Holy Toledo comes from”, we turned a corner and came face to face with a towering spectacle: the monstrance.

Encased in glass, it gleamed with over 400 pounds of gold and silver, crafted into a gothic tower taller than a man. It’s only used once a year, during the Feast of Corpus Christi, when it’s paraded through the streets in a grand procession.

Earlier that morning, we’d noticed long white cloths strung between the buildings above Toledo’s narrow streets -they’re hung each year to honor the monstrance’s path through the city.

Our guide pointed upward and explained a quiet tradition: when a cardinal or bishop is buried here, his red galero (hat) is suspended from the ceiling above his tomb. It stays there until it decays and falls—symbolizing humility and the fleeting nature of earthly power.

As we rounded the back of the altar, we found ourselves looking up in awe at one of the most theatrical and unexpected sights in any cathedral — the Transparente. Commissioned in the early 1700s, this Baroque masterpiece was created to let light shine directly onto the tabernacle below. A large hole was carved through the cathedral ceiling — yes, literally through the stone vault — and the resulting shaft of light spills across a whirlwind of carved angels, saints, and clouds.

The surrounding fresco depicts the Glory of the Holy Sacrament, as if heaven itself is opening above the high altar. You can almost hear trumpets in the background. It was meant to inspire devotion, but also to draw attention to the Eucharist — the true “light” of the church.

After the tour, we were starving. Javier had pointed out a local spot and we found it: La Bodega.

I know this might look like one of those “Look what I got for lunch!” posts, but trust me—this is about way more than a burger. This was a cultural experience.

In Spain, lunch is the biggest meal of the day. But they don’t eat until 2 or 3 o’clock in the afternoon, and by then, I’m shaky, starving, and ready for something hearty. The only problem? What Americans think of as a “big meal” (a big hunk of meat, some veggies, maybe a potato) is not how they do it.

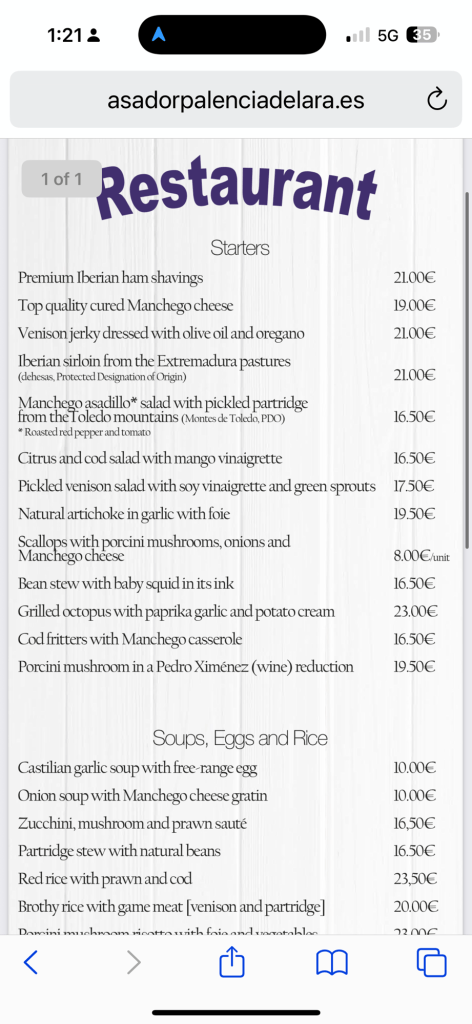

Even though lunch is their main meal, it’s a slow, leisurely two-hour affair—nothing rushed, which I actually loved. But the menus? Completely unfamiliar. And somehow, the moment there’s a white tablecloth on the table, it all gets even more confusing.

Back in Madrid, I ordered Iberian ham, thinking I was getting a thick, juicy slice of ham. What arrived was a few thin, delicate slices—more like charcuterie—with a little basket of bread to tear apart and nibble with it. Beautiful, sure. Filling? Not so much.

So here we are in Toledo. We sit down—white tablecloths again—and the menu’s just as puzzling. I’m scanning for protein and veggies and not seeing anything that makes sense. That’s when Bob saves the day. He somehow figures out there’s a completely separate bar menu in the front of the restaurant—new menu, new seating, maybe even a whole new business for all I know. But that’s the only place we can order a hamburger.

It made zero sense, but it was so worth it. That hamburger was the best lunch decision of the whole trip.

So yes, I’m posting food photos. But not because I think you need to see my lunch—because this was one of those “now we get it” moments in the middle of learning to travel like a local.

We begged for forgiveness, grabbed our sangrias and relocated.

They greeted us with a tray of complimentary pig ears.

We smiled politely, passed them around the table. I dont think any of us were brave enough to try them. We waited for the burger—and it didn’t disappoint. Juicy, perfectly seasoned, and absolutely hit the spot. Maybe it was travel fatigue or just pure nostalgia, but it tasted like the best hamburger we’d ever had. The fries were good too, just didn’t get a lot but it all was heavenly.

After lunch we got settled in while the guys walked to one of the bridges,

They also went to the El Greco museum with some El Greco paintings.

Before heading out for dinner, we made our way down to the basement level of our hotel.

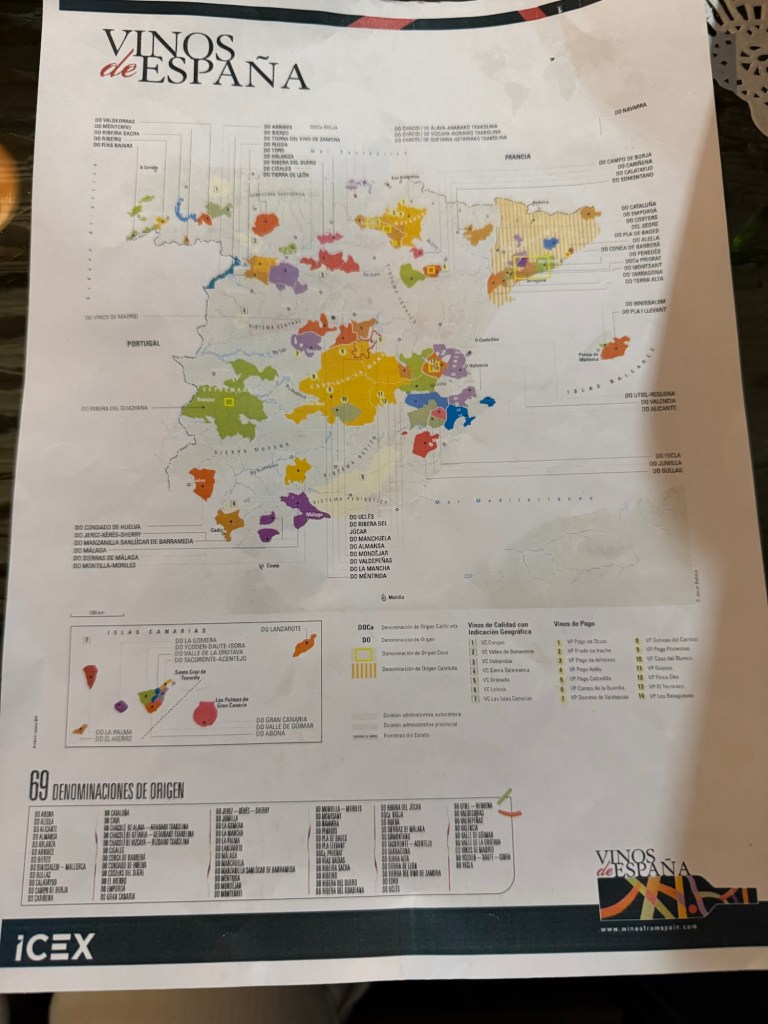

Javier greeted us with a spread of fresh baguettes, Manchego cheese, and slices of venison chorizo. Two bottles were uncorked: a bold Rioja and a smooth Ribera del Duero. As he poured, Javier shared stories about the winemakers and regions with the kind of warmth that made us want to savor every sip.

The setting was rustic, the wine was flowing, and the company was even better. A perfect pause before our final night in Toledo.

After this treat we headed to dinner, which was a struggle because no one spoke English. Lots of laughs but we found a few veggies in the salad.