Today started early, 6:30, we were to meet with long pants, tucked into our socks, rain jackets and lots of bug spray, lots of water. They promised to bring us breakfast around 8am.

We headed toward the spot where the brown waters of the Amazon meet the black waters of a tributary — a natural mixing zone that our guide said was the best place to spot dolphins. From a distance, you could see the line where the two rivers met but didn’t blend — one side milky brown from the silt and clay carried down from the Andes, the other dark and glassy like steeped tea.

The brown water, called whitewater, is heavy with minerals and nutrients, while the blackwater is clear but stained by decaying leaves and plants. Where the two come together, fish thrive in the nutrient-rich mix — and wherever there are fish, there are dolphins.

This is where the gray river dolphins, called tucuxi, and the pink river dolphins, or botos, come to feed. The gray ones look like smaller, friendlier cousins of the bottlenose dolphins we see off Hilton Head. They’re sleek and sociable, surfacing in pairs or trios, their curved dorsal fins slicing the water in gentle rhythm.

The pink dolphins, though, are harder to find and almost prehistoric in appearance — larger, rounder, with long beaks and soft, flexible bodies built for the flooded forest. They’re solitary and mysterious, surfacing alone with a puff of air that sounds almost human before slipping back beneath the surface. Their fins are short and hard to spot, and by the time you turn your head or raise your camera, they’re already gone.

We waited quietly, scanning the water. You could hear them before you saw them — a sudden exhale, a swirl, a flash of color just under the surface. We tried again and again to catch a photo, but every time the lens focused, the river was still. The botos seemed to appear only long enough to remind us we were guests in their world — and then vanish, leaving behind nothing but ripples on the brown and black divide.

You get a taste of our morning tour with Roger our naturalist and his joke about photos vs video

Our guide spotted a sloth! He explained that this one was a Brown-throated three-toed sloth (Bradypus variegatus), the most common species in the Peruvian Amazon. They’re known for their gentle faces, rounded heads, and small, calm eyes — almost as if they’re smiling. Unlike the two-toed sloth, which is nocturnal, this species is active during the day, making it a bit easier (though still rare) to spot in the wild. Their fur hosts a thin layer of green algae, which helps them blend perfectly with the trees — nature’s slowest-moving camouflage.

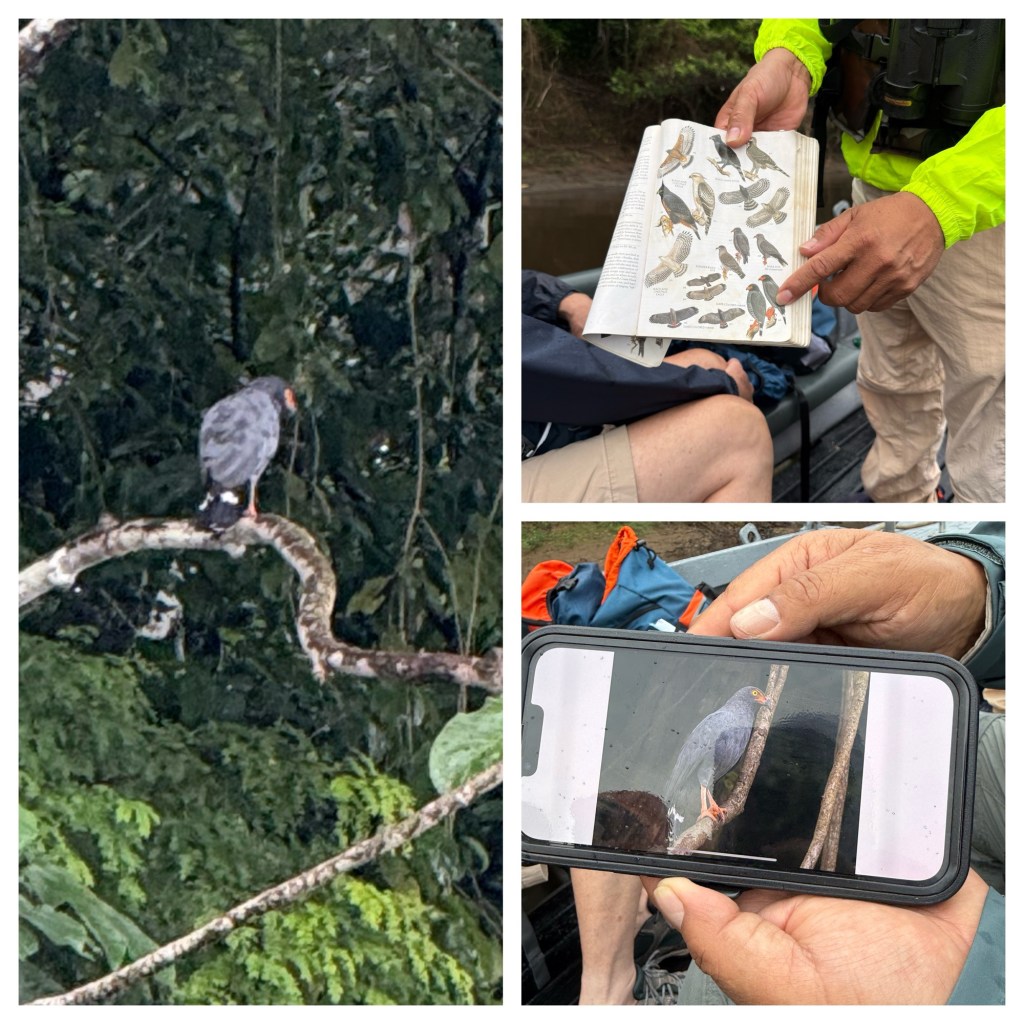

Next up we went bird watching.

Distinguishing features: pure white plumage, black legs with yellow feet, and a slender black bill with a yellow base.

High in the Amazon canopy, a flash of scarlet caught our eye — a Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock. These striking birds are almost surreal in color, their feathers a vibrant blaze against the deep green jungle. Males are known for elaborate courtship displays, gathering in small “leks” where they perform hopping dances and low calls to impress females.

Spotting this rare bird felt like winning the jungle lottery. Our guide excitedly showed us a reference photo on his phone to confirm the ID — the slate-gray feathers, bright orange beak and legs were unmistakable. These secretive forest hunters prefer the dense canopy, where they sit motionless and wait to ambush small prey.

Yellow-rumpled Cacique have jet-black plumage and brilliant yellow rump and tail feathers make them stand out even against the muddy riverbanks. These social birds often build long, hanging nests in colonies high in trees, usually near water to deter predators.

Listen to their weird sounds.

These birds are Wattled Jacanas (Jacana jacana) — sometimes called Jesus birds because they appear to walk on water, thanks to their extremely long toes that let them stride across floating vegetation.

Along the riverbank, the tall rows of corn reflect the ingenuity of Amazonian life and the rhythm of the seasons. Families plant these crops on nutrient-rich floodplain soil after the river recedes at the end of the rainy season, taking advantage of the fertile silt left behind. As the dry season settles in, the fields flourish under the sun, providing food for households and sometimes for trade with nearby villages. The corn, often a traditional local variety, is used in daily meals or fermented into chicha, a regional drink. This simple riverside field embodies a sustainable way of living—working in harmony with both the river’s rise and fall and the alternating cycles of rain and drought that define life along the Amazon.

These houses are built high above the river to adapt to the Amazon’s extreme seasonal flooding, which can raise water levels by up to 30 feet during the rainy season. The elevated design keeps homes dry, protects against snakes and insects, allows cooling air to circulate underneath, and helps preserve the wooden structure from rot and decay. During the dry season, the river recedes and wide banks are exposed, but when the rains return, these stilted homes remain safely above the rising water.

Next up we park our boats next to the other group and suddenly like magic breakfast appears!!

What an experience! I couldn’t believe we had a nice tray of food with more food than you could eat. We were thrilled and happy!

After breakfast we continued to explore the Amazon in Part II.