The confluence is where two rivers meet and join to form a larger one—in this case, the Marañón and Ucayali Rivers coming together to create the Amazon. The contrast is striking: one river carries dark, tannin-rich water, while the other runs a lighter brown from Andean silt. They flow side by side for miles before fully blending, creating a visible line in the water.

We return for breakfast.

After breakfast, it was time to try on the wellies they had for our jungle walk. I came out to test mine, but immediately noticed a woman stretched out across the benches, one of the areas where we would sit down to try on the boots. I wasn’t sure where she’d come from, but our medic, Marcus, was beside her, administering an IV. She looked distraught. We soon learned she was from a nearby village and had been bitten by a venomous snake called a Fer-de-Lance. The crew quickly used one of our skiffs to rush her to Nauta for medical care, and later to a hospital in Iquitos. Word eventually came that, two weeks later, she was improving little by little.

Both teams squeezed into the remaining skiff, and while we waited for the other one to return, we cruised slowly along the riverbanks, scanning the trees for movement. The guides told us we’d be fishing first, but we needed to spread out between both boats—so for now, we had to wait.

While we wait for the second skiff we look for wild life. First one we spotted was a brown-throated three-toed sloth, its fur a mix of soft browns and grays that blended so well with the bark it almost disappeared. Our guide explained that the Amazon is also home to two-toed sloths, which are slightly larger, lighter in color, and more active at night. The three-toed sloths, like this one, are usually seen during the day, draped over branches and moving at their own unhurried pace. This one barely stirred, just turned its head as if to glance at us before melting back into stillness.

As we moved further down the river we spotted a few woolly monkeys. They get their name from its dense, soft fur, which looks a bit like a plush coat—usually brown, gray, or reddish, depending on the species. These monkeys are medium to large in size and have strong, prehensile tails that act almost like a fifth limb, helping them balance and swing gracefully through the treetops.

They live high in the canopy and are known for being playful and social, often moving in small groups. Their diet includes fruit, leaves, seeds, and the occasional insect. Because they’re sensitive to habitat loss and hunting, they’re considered vulnerable in many areas of the Amazon. Seeing one in the wild is a real treat—it usually means you’re deep in untouched forest.

When the second skiff finally appeared, we were able to split up and start piranha fishing. We used small chunks of raw beef as bait and spread out along the edge of the river. I’ve never caught a fish in my life—once I fished in the Delaware Bay with my grandfather and actually had a flounder on the hook, but I didn’t know what to do, so it ate the bait and swam away. This time, I listened carefully to the instructions and caught my very first fish—a tiny river catfish with smooth skin and long whiskers. The guides told us not to touch it because these catfish have sharp, venomous spines near their fins that can cause a painful sting if you grab them the wrong way. The whiskers, called barbels, help them feel their way around and “taste” the water since it’s so murky in the Amazon. The rest of the time, I tried to catch a piranha but had no luck. They nibbled the bait right off the hook and got away every time. Meanwhile, Dr. Gary and our guide were reeling them in one after another, so I focused on grabbing some photos instead.

Roger and his group came up on our group, we had the other naturalist Usiel. Next up our hike through the jungle.

It was soooo hot and buggy. We had to wear our boots to walk through.

Usiel spotted the pygmy marmoset, the smallest monkey in the world, only about five to six inches long. Found throughout the Amazon Basin, they cling to tree trunks with sharp claws, feed on tree sap and insects, and move with incredible speed. Their high-pitched chatter and quick darting movements help them stay safe from predators and even defend their feeding spots when larger monkeys, like woolly monkeys, come too close.

This giant kapok tree, or Ceiba pentandra, is one of the Amazon’s most iconic species. Its wide buttress roots anchor it in the thin jungle soil and create a natural cathedral beneath the canopy.

Wilfredo mentioned he’d recently seen a snake hiding beside a tree like that, so we did not linger.

Shortly after this point our guides turned us back to the skiffs, the monkeys were starting to get territorial and it was time to leave!

Next, we were invited to an ancestral cooking class where they showed us how to prepare catfish for soup. The fish’s skin was like armor—thick and tough—so they demonstrated how to carefully remove it before filleting the meat to add to the broth.

They also introduced us to suri grubs, the creamy white larvae of the palm weevil found inside decaying palm trunks. Rich in protein and fat, these grubs are considered a delicacy in the Amazon as well as an aphrodisiac. Jon was brave enough to try one raw—it’s said to have a buttery, nutty taste with a hint of coconut.

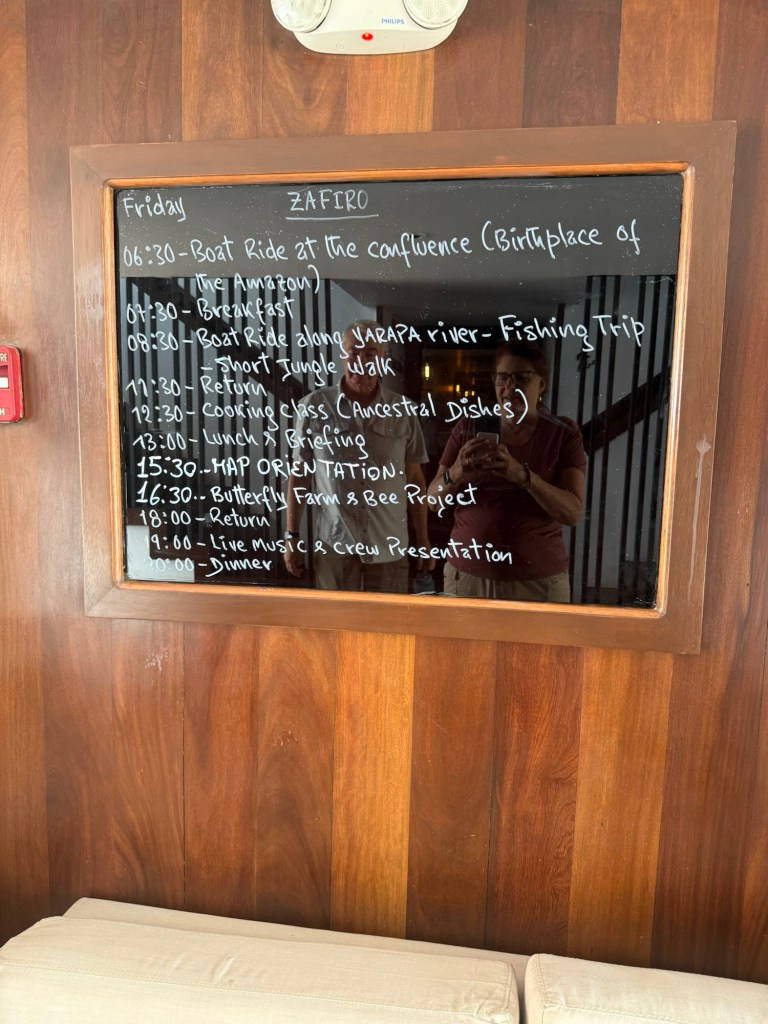

This concludes Part 1, we have so much more left for our last full day. Visit a Butterfly farm, and so much more.